Umetnost je često prethodila sveukupnom razvoju, ali i savezima među društvima, tako da verujem da, ako nema političkog uplitanja, čak i u slučaju između naša dva društva, umetnost će prethoditi političkim procesima.

To se odvija u našim svakodnevnim životima, jer mi na umetničkoj sceni Balkana imamo mnogo toga zajedničkog. Kao takvi, na međunarodnim izložbama u inostranstvu umetnici sa Balkana uvek se drže zajedno. Na taj način otvaramo put za prevazilaženje predrasuda i mržnje između balkanskih društava, iako je gotovo nemoguće učiniti više kada volja donosilaca odluka nedostaje, ukazuje Alban Muja, istaknuti kosovski umetnik, u intervjuu za Danas.rs u okviru projekta Druga strana Kosova.

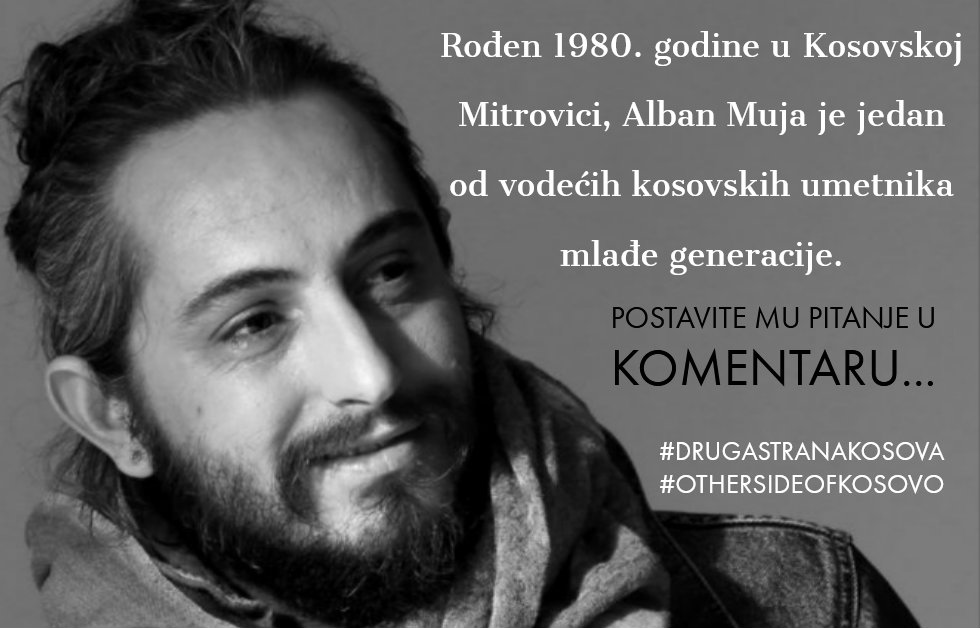

Alban Muja je rođen u Mitrovici na Kosovu 1980. godine. Trenutno živi u Prištini, na Kosovu, gde je završio Fakultet likovnih umetnosti. Njegov rad pokriva širok spektar medija, uključujući video instalacije, kratke filmove, dokumentarne filmove, crteže, slike i predstave, a široko je izložen na međunarodnom nivou, pa ga zato očekuje i svečano otvaranje kosovskog paviljona pod nazivom „Porodični album“ 9. maja u Arsenalu, u Veneciji.

Projekat „Druga strana Kosova“ ima za cilj da približi kosovskoj i srpskoj javnosti informacije koje nisu plasirale političke elite, ni s jedne strane, već nezavisni građani i ima za cilj povezivanje kosovske i srpske kulturne scene koja je nedovoljno zastupljena u medijima.

- Pitanja novinara Danasa

U čemu nalazite inspiraciju?

– Poslednjih godina, na moje radove, u velikoj meri su uticali procesi društvenih, političkih i ekonomskih transformacija na Kosovu i u regionu. Pokušao sam da istražim i istorijske i društveno-političke teme, kao i da ih povežem sa svojom pozicijom danas na Kosovu. Više verujem u istraživanje različitih tema nego u inspiraciju, ali ako bismo već upotrebili reč „inspiracija“, onda ona dolazi iz mesta u kome se živi i suočava sa svakodnevnim životom. To je inače, moj glavni fokus, u proteklih nekoliko godina, koji ostvarujem putem različitih medija.

Pročitala sam da na Vaš rad utiču društveni i politički procesi transformacije, možete li opisati alate koje koristite i način na koji stvarate umetnost? Šta kritikujete i za šta se zalaže Vaša umetnost?

– Političke, ekonomske i socijalne transformacije dešavale su se na Balkanu u poslednjim decenijama, pa tako i u mojoj zemlji, na Kosovu. Konačno smo slobodni, stoga smatram da kao umetnici ne možemo ostati ravnodušni i da se ne bavimo tim temama, jer čak i da se ne bavimo njima, one bi se bavile nama i našim svakodnevnim životima. Kritičari su često doživljavali te radove i procese kroz koje smo prolazili kao politički angažovane, ali ja i dalje smatram veliki deo tih projekata za humane, ljudske projekte.

U prethodnim projektima pokušavao sam da držim određenu distancu od sopstvenog iskustva koje sam stekao u detinjstvu i iskustva moje porodice, fokusirajući se umesto toga na posledice koje su usledile nakon završetka rata na Kosovu. Svakojake istorije – moje lične ili one koje su ljudi oko mene iskusili – bile su one s kojima sam se bavio, zato što mi kao društvo nismo imali normalnu prošlost, kao druge nacije širom sveta, jer smo se suočili sa nedostatkom najosnovnijih stvari u životu.

Često sam iz trenutne pozicije pokušavao da detaljnije proučim takve teme. Pitanja poput nedostatka normalnog obrazovanja, jer, kao što je poznato, moja generacija – zajedno sa nekoliko drugih generacija na Kosovu, obrazovanje je sticala tokom „paralelnog sistema“, učeći u kućama-školama, koje su u to vreme, od strane režima, bile posmatrane kao „ilegalno obrazovanje“, zato što smo želeli da se obrazujemo na našem jeziku. Druga tema je bila onemogućenost da se direktno kontaktiraju članovi albanskih porodica koji žive sa druge strane albansko-jugoslovenske granice. Odsustvo državnih institucija, koje vas tretiraju isto kao što tretiraju građane drugih nacionalnosti, nedostatak medija na sopstvenom jeziku za vreme odrastanja i u vreme tinejdžerskih godina. Sve je to moralo ilegalno da se radi.

Verujem da o ovim temama treba diskutovati tiho i bez emocija. Kao dete koje je iskusilo rat i izbeglištvo, u početku nisam bio svestan onoga kroz šta smo prolazili. Nekog nekog vremena, pokušao sam nepristrasno pristupiti političkim, ekonomskim i društvenim promenama, koje su nama bile pozitivne. Često sam to činio kroz imena dece na Kosovu, jer su ona, u zavisnosti od načina života i političkih pozicija, ukazivala na situaciju. Ako pogledamo osamdesete, imena se uglavnom odnose na nedostatak slobode, nedostatak mogućnosti za obrazovanjem, nedostatak mogućnosti upotrebe maternjeg jezika, ponosa zastave, pa su i imena prilagođena ovim fenomenima. Politička i ekonomska transformacija uočljiva je u davanju imena deci.

Ako ne grešim, izlagali ste u Novom Sadu. Da li ste izlagali u Beogradu? Ako ne, da li biste hteli i kakav je Vaš utisak o odnosima između kosovskih i srpskih umetnika?

– Bio sam jedan od umetnika koji su učestvovali na izložbi u Novom Sadu, pod nazivom ‘Izuzetak’. Prošla je dobro, uz razne debate ali generalno dobre. Nakon toga ista izložba je bila planirana u Beogradu, ali nikada nije otvorena zbog protesta i reakcija, ali i zato što su nacionalističke grupe u Beogradu uništile deo izložbe. Bila je to dobra ideja, da četiri kustosa iz Beograda i Novog Sada naprave saradnju između umetničke scene Srbije i Kosova. Međutim, grupa ljudi to nije želela, intervenisali su i zaustavili otvaranje, pa čak i uništili umetničko delo. Cela ideja je zapravo započeta dok sam bio u umetničkoj rezidenciji na Kuda.org, u Novom Sadu, gde sam se dobro proveo i upoznao sa stvarnošću. Tako smo započeli saradnju, ali su je drugi zaustavili.

Poslednji put kada sam bio u Beogradu, u decembru 2017. godine, takođe sam učestvovao u diskusiji o (nedostajućoj) saradnji između dve umetničke scene, koju je organizovao Centar za kulturnu dekontaminaciju, 20 godina nakon izložbe „Pertej“ (Beiond), koju je sa kosovskim umetnicima organizovala ista institucija. Bilo mi je indikativno to što se razgovaralo o svemu osim o tome šta se dogodilo devedesetih godina na Kosovu. Istog dana, ponovo je otvoren Muzej savremene umetnosti u Beogradu. To sam doživeo kao dobru vest za umetničku scenu celog regiona. Međutim, tu su se našli umetnici i reditelji umetničkih institucija iz svih delova regiona – osim sa Kosova. Verujem da ove mentalitete treba prevazići i saradnja treba da počne – ne zaboravljajući prošlost, već gledajući u budućnost. Pre nego što dođe do takve saradnje, greške koje su napravljene u prošlosti treba da budu prihvaćene, jer ne znam u kojoj meri su vaši čitaoci i umetnička scena uopšte informisani, ali i danas, čak i nakon 20 godina, svi artefakti iz Muzeja Kosova koji su 1999. godine konfiskovani od strane Miloševićevog režima, još se nalaze u Beogradu, a vlasti tamo nemaju ni najmanje volje da vrate ove predmete kući gde pripadaju. Moraju se dogoditi saradnje, ali one moraju biti poštene i prošlost mora biti priznata. To uključuje i izvinjenja za sva nedela koja su počinjena nevinim ljudima.

Šta bi, prema Vašem mišljenju, trebalo najpre i prioritetno učiniti kako bi se odnosi Srbije i Kosova normalizovali?

– Kao što sam ranije rekao, najvažnije je da Srbija objektivno prihvatiti činjenice o stvarnosti koja se dešavala u prošlosti. Bez tog prihvatanja biće ogromnih problema u napretku i normalnim odnosima između Srbije i Kosova. Ne može biti napretka sve dok smo neiskreni u odnosu na prošlost i pokušavamo blokirati jedni druge, sada i za budućnost. Ponovo ću reći: odnosi između pojedinih umetnika su korektni i respektabilni, posebno oni koji svoje radove predstavljaju u inostranstvu, ali to bi trebalo izvesti i u drugim oblastima.

Kako ocenjujete proces normalizacije koji trenutno vode vlasti u Prištini i Beogradu?

– Mislim da je od samog početka bilo problema. Čak ni oni dogovori koji su napravljeni nisu imali odgovarajuću implementaciju i često su bili štetni za obične ljude. Na primer, jedan od sporazuma postignutih u procesu međunarodnih pregovora o posredovanju bio je o slobodi kretanja, nešto što bi trebalo da bude fundamentalno. Ovaj sporazum omogućava građanima Kosova da putuju kroz Srbiju samo automobilom ili autobusom. Ako želim da putujem u Srbiju ili iz Srbije avionom ili čak vozom, to mi nije dozvoljeno, a za putovanje automobilom moram da kupim privremene tablice. Ja to ne vidim kao proces normalizacije, već kao komplikaciju. Trebalo bi sklopiti sporazume za naša društva, a ne za političke dobitke pojedinaca, jer smo mi ti koji su povređeni u takvim situacijama. Verujem u normalizaciju, ali moraju postojati jake međunarodne garancije, uz garancije manjinskih prava, kako na Kosovu tako i u Srbiji. Prošlost nas je naučila da ako se različite grupe ljudi u društvu ne tretiraju jednako, to se vraća da nas progoni.

Da li je moguće da proces normalizacije odnosa Kosova i Srbije okončaju političke elite koje su bile aktivne tokom sukoba devedesetih godina?

– Čini se da ćemo imati manje-više iste političke elite na vlasti, ili njihove naslednike. Ponekad se čini da su neki od ovih političara otvoreniji i spremniji da rade na normalizaciji, ali često vidimo ista lica u pozadini. Verujem da, pre svega, društva treba da se razvijaju i da biraju prave vođe. Bez toga se teško vidi napredak. Veoma je teško napredovati dok postoje ljudi koji pokušavaju da stvaraju politiku čak i sa telima ljudi nestalih tokom rata, a Kosovo ima veliki broj njih. Pre nekoliko dana čuo sam izjavu vašeg predsednika, koja me je podsetila na poznatu nacionalističku retoriku iz 1990-ih. On je rekao da se nada da će uskoro Kosovo dobiti viznu liberalizaciju, pa će veliki broj Kosovara napustiti zemlju i zaustaviti stanovništvo na Kosovu. Verujem da su takve izjave štetne i skandalozne, jer moramo uvideti kako da normalizujemo naša društva, a ne da unosimo još više mržnje. Nadam se da će, uz pritisak međunarodne zajednice, političari koji su sada na vlasti na obe strane doći do dogovora. Ne mogu da vidim drugi put za Kosovo i Srbiju, jer moramo sarađivati jedni s drugima, i nema drugih pozitivnih scenarija osim da idemo napred zajedno sa drugim evropskim društvima. A mislim da za njima zaostajemo daleko.

Pitanja umetnika Vladimira Nikolića:

Pitanja umetnika Vladimira Nikolića:

Koliki deo svoje umetničke produkcije realizujete na Kosovu?

– Većina mojih projekata se realizuje na Kosovu i sa timom sa Kosova, osim nekih specifičnih projekata, i onda kada sam privremeno boravio van Kosova. Verujem da mi kao umetnici moramo reagovati na to gde živimo sa fokusom na istraživanje. Istraživanja su me često slala van Kosova, ali u većini slučajeva naše umetničke „akcije“ dolaze odavde.

Sa kojom ex-Yu scenom imate najviše kontakta?

– U svim zemljama bivše Jugoslavije imam mnogo kontakata, posebno sa umetnicima, kustosima i drugim ljudima koji dolaze iz sfere umetnosti. Veliku saradnju sam imao u Sloveniji, posebno u Ljubljani, ali i u Hrvatskoj. To su bila prva mesta u regionu koja su otvorila svoja vrata za moje izložbe i druge prezentacije. Oduvek govorim da bi bez podrške ove dve umetničke scene meni bilo mnogo teže. Međutim, manje imam iskustva u drugim zemljama bivše Jugoslavije.

Šta je najviše uticalo na Vašu odluku da ostanete u Prištini pored toliko prilika da se smestite u neki udobniji deo sveta od ovog našeg?

– Posao koji obavljam ovde ne tera me da ne razmišljam o napuštanju Prištine, jer je većina mojih projekata vezana za Kosovo. Možemo mnogo da putujemo, ali na kraju moramo da se vratimo i reagujemo ovde. To je manje-više moj slogan kada razgovaram sa mlađim umetnicima ili sa mojim učenicima. Razmišljao sam o promeni okruženja nekoliko puta, posebno kada sam bio izvan Kosova duže vreme u različitim rezidencijama, jer sam već duže vreme bio pola godine na Kosovu, a pola godine izvan njega. To mi je bilo veoma prijatno iskustvo i pomoglo mi je u radu. Kako sa Kosova, tako i iskustva i uticaji iz inostranstva pomažu. Ne kažem da ću zauvek ostati na Kosovu, jer sve zavisi od posla, ali za mene je do sada realizacija projekata bila mnogo lakša ovde. Iako postoje izazovi za umetnika koji živi u malom mestu, verujem da sam za sada zadovoljan životom u Prištini i čestim radnim putovanjima.

- Pitanja sa društvenih mreža:

„Neka umetnost uništi barijere između ljudi“, kaže jedan od komentara, šta mislite o tome? Verujete li da umetnost može učiniti više dobra za ljude nego što to može politika i zašto?

– Pročitao sam neka od pitanja u komentarima i ovo je bilo jedno od onih koje mi se svidelo, za razliku od nekih neprijatnih pitanja, koja se nalaze u odeljku pod nazivom „Druga strana Kosova“. Imao sam mali problem sa temeljnim razumevanjem naslova ovog odeljka. Istina je da smo, kao i svako drugo društvo, multidimenzionalni, međutim, pitam se: Koja je „Prva Strana Kosova“? Ona o kojoj svakodnevno slušamo u medijima u Beogradu i ona koju su kosovski Albanci i Kosovari generalno navikli da čuju?

Sada, da odgovorim na pitanja čitalaca – umetnost je često prethodila sveukupnom razvoju, ali i savezima među društvima, tako da verujem da, ako nema političkog uplitanja, čak i u slučaju između naših dvaju društava, umetnost će prethoditi političkim procesima. To se odvija u našim svakodnevnim životima, jer mi na umetničkoj sceni Balkana imamo mnogo toga zajedničkog. Kao takvi, na međunarodnim izložbama u inostranstvu umetnici sa Balkana uvek se drže zajedno. Na taj način otvaramo put za prevazilaženje predrasuda i mržnje između balkanskih društava, iako je gotovo nemoguće učiniti više kada volja donosilaca odluka nedostaje.

Kako se odvijaju pripreme za Bijenale u Veneciji?

– Možete zamisliti koliko je bitno biti deo Venecijanskog bijenala. Predstavljanje sopstvene zemlje, osim užitka, daje vam i veliku odgovornost, jer ne predstavljate samo sebe i svoje ime, već i mesto iz koga dolazite, vašu naciju. To je bio glavni fokus i predstavljao je najveći zadatak tokom priprema. Ova prilika me čini veoma srećnim, ali me je faza pripreme učinila mnogo svesnijim važnosti deljenja ličnih iskustva s publikom Venecijanskog bijenala, iz razloga što, barem za vreme prezentacija, možemo biti jednaki sa drugim državama (u smislu prezentacije). Imamo odličan tim i imali smo punu podršku Ministarstva kulture, što je pomoglo. Međutim, sam projekat je bio veoma izazovan. Zahvaljujući našem timu, komesaru Arti Agani, kustosima Vincetu Honoreu i Anji Harrison, i mnogim drugima koji rade u paviljonu, mislim da ćemo uspeti i nadam se da ćemo imati dostojanstvenu prezentaciju.

Šta za Vas znači biti umetnik na Kosovu?

– Biti umetnik sa Kosova je izazov, kao na celom Balkanu, jer se umetnost u društvu često ne smatra prioritetom zbog fundamentalnih problema. Mora se priznati da postoji podrška za određene projekte, ali postoji nedostatak umetničkih tržišta, posebno kolekcionara umetnina i komercijalnih galerija koje uvode i prodaju dela umetnika. Ovaj fenomen nije prisutan isključivo na Kosovu i Balkanu, već i izvan njega, ali u našem regionu je to očiglednije. Ono što nas izdvaja u regionu svakako je ogromna količina originalnih i zanimljivih tema, samo treba da pronađemo načine da na njih ukažemo. Zapad ima nešto svoje, ali i mi imamo nešto.

***

ENGLISH VERSION

- Questions asked by Danas daily journalists:

What inspires you to create art?

– In my works in recent years I have been largely influenced by the processes of the social, political and economic transformations in Kosovo, and in the region. However, I have also tried to explore historical and social-political themes, as well as to link them to my position today in Kosovo. Today I believe more in researching various topics than in the inspiration, and if it can be called ‘inspiration’, then I believe that it should be the place where one lives and faces the everyday life. This has been my main focus for the last few years, which I have tried to realize (accomplish) in different media.

I read that your artistic practice was mostly influenced by the social and political transformation processes. Can you describe the tools that you use and the way you create art? What do you criticize most and what does your art stand for?

– Political, economic and social transformations have been happening to a great extent in the Balkans in recent decades, including my own country, Kosovo. Finally we are free, therefore I believe that as artists we could not remain indifferent and not address such topics, because even if we didn’t deal with them, they would deal with us and our everyday lives.

Critics also have often considered these works to be the processes through which we have been going through, but I still consider a large part of these projects human projects.

In my previous projects I have constantly tried to keep a certain distance from my own experience as a child and the experience of my family, focusing instead on the consequences that came after the war ended in Kosovo. Diverse histories – my personal ones or those of the people around me – have been the ones I have dealt with, because we as a society did not have a normal past like other nations around the world, since we have faced the lack of the most elementary things in life.

I have often tried to do a more in-depth study of such topics from my current position – issues such as lack of normal education, because as it is known, my generation along with several other generations in Kosovo accomplished most of the education during the “Parallel System”, learning in houses-schools, at that time considered by the regime „illegal education“, since we wanted to be educated in our own language. Another topic is the impossibility of direct contacts between separated Albanian family members living on the two sides of the Albanian-Yugoslavian border, the absence of state institutions that treated you the same as they treated the citizens of other nationalities, the lack of media in your own language at the time you were a child and teenager.

All this had to be done “illegally”.

I believe that these topics should be addressed and discussed quietly and without emotions. As a child who was experiencing war and being a refugee, at first I was not aware of what we were going through, but after some time I have tried to regard with an unbiased approach the political, economic and social changes which were fortunate for us. I have often done this through the names of children in Kosovo, because depending on their lifestyle and the political positions they/we have had, the names indicated the situation. If we look at the 1980s, the names mainly address the lack of freedom, possibilities for education, mother tongue use, the pride of the flag, and names adapted to these phenomena. Political and economic transformations were also observed in the given names of children.

If I’m not wrong, you were exhibiting in Novi Sad (what was your experience there?), have you ever had an exhibition of your art in Belgrade? If not, would you like to, and what is your impression about the relations between Kosovo and Serbia artists?

– I was one of the artists participating in the exhibition in Novi Sad, titled ‘Exception’, which went well, with various debates and generally good. Nevertheless, afterwards the same exhibition planned in Belgrade was never opened because of the protests and reactions as well as the destruction of a part of the exhibition by a nationalist group in Belgrade. It was a good idea of four curators from Belgrade and Novi Sad to start the cooperation between the art scene in Serbia and the art scene in Kosovo. However, a group of people and some of the powerful people in the political establishment in Serbia who did not like it as well, intervened and prevented the opening, and even destroyed an artwork. In fact, the whole idea had started while I was at an artists’ residence in Kuda.org, in Novi Sad, where I spent a good time and I was introduced to the reality there, so we began this cooperation which was halted by the others.

There are also individual collaborations between artists and nongovernmental organizations, but not institutionally, as there is often a lack of willingness in Belgrade to respect the reality that exists today in Kosovo. By all means, I believe that before a healthy cooperation can start we necessarily have to talk about our past and we should not be afraid to truthfully analyze the reality that happened in Kosovo, especially during the 1990s.

The last time I was in Belgrade, in December 2017, I also participated in a discussion regarding the (missing) collaboration between the two art scenes, organized by the Center for Cultural Decontamination, 20 years after the exhibition “Përtej” (Beyond), which was organized with Kosovar artists by the same institution. The fact that there were discussions about everything, apart from what happened in Kosovo in the 1990s spoke volumes to me. On the same day there was the re/opening of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, which I thought was good news for the entire art scene of the region, and there were artists and art institutions’ directors from all over the region – except from Kosovo. I believe that these mentalities should be overcome and collaboration should start – not by forgetting the past, but looking out to the future.

Before such cooperation could take place, the mistakes that were made in the past should be accepted because I do not know to what extent your readers and the art scene in general are informed, but even today, even after 20 years, all the artifacts of the Museum of Kosovo which were confiscated in 1999 by the Milosevic regime are still situated in Belgrade, and the authorities there do not have the slightest willingness to return these artifacts back home where they belong. Collaborations must happen, but they must be honest and the past has to be acknowledged, including the apologies for all the wrongdoings to innocent people.

In your opinion, what should be the priorities for the sake of the normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo?

– As I have said above, the most important issue is that Serbia has to objectively accept the facts of the reality that has happened in the past. Without this acceptance there will be huge problems with going forward and having normal relations between Serbia and Kosovo. There can be no progress as long as we are insincere regarding the past and try to block each other now and for the future. I’ll say it again: the relationships between the individual artists are correct and respectable, especially between those who present their works abroad, but this should be done in other areas as well.

What do you think about the process of normalization that is currently being undertaken by the authorities in Pristina and Belgrade?

– I believe there were problems from the very beginning. Even those agreements which have been reached are not implemented properly and they are often harmful to the ordinary people. For example, one of the agreements achieved in the process of international mediation talks was about the freedom of movement, something I believe should be fundamental. This agreement allows us, citizens of Kosovo, to travel through Serbia only by car or by bus. If I want to travel to Serbia or from Serbia by airplane or even by train, I am not allowed to do so, while for traveling by car I have to buy temporary plates. I do not see this as a process of normalization, but of complication.

Agreements should be made for our societies and not for political gains of particular individuals, as we are the ones who are affected in such cases. I believe in normalization, but there must be strong international guarantees, with minority rights guarantees both in Kosovo and in Serbia. The past has taught us that if the different groups of people in a society are not treated equally, this will come back to haunt us.

Is it possible that the normalization of relations between Kosovo and Serbia might be achieved by the political elites that were active during the 1990s conflicts?

– It seems that we will have more or less the same political elites in power, or their heirs. Sometimes some of these politicians seem to be more open and ready to work towards the normalization, but we often see the same faces in the background. I believe that above all societies should evolve and elect the right leaders. Without this happening, it is difficult to see progress. While there are people who try to make politics even with the bodies of missing persons during the war, and Kosovo has a large number of them, it is very difficult to progress.

Several days ago, I heard a statement of your president that reminded me of a well-known nationalist statement of the 1990s. He said that he was hoping that Kosovo would soon obtain visa liberalization in order for a large number of Kosovars to leave the country and halt the growth of the population in Kosovo. I believe such statements are damaging and scandalous, as we have to find the way to normalize the relations between our societies, and not to incite even more hatred.

I hope that due to the international community pressure the politicians who are now in power on both sides will come to an agreement. I cannot see another way for Kosovo and Serbia, because we have to cooperate with each other, and there are no other positive scenarios except going forward together with other European societies. I think we are lagging far behind.

- Questions from the social media:

https://www.instagram.com/p/BvzzMLdBKMd/

„Let the art destroy the barriers between the people“, says one of the comments, can you reflect on that? Do you believe that art can do more good for the people than the politics and why?

– I have read some of the questions in advance and this is one of those I like, unlike some other unpleasant questions in the section you have called „Druga Strana Kosova“. I have a little problem with understanding thoroughly the title of this section.

It is true that, as every other society, we are also multidimensional, but my question would be: Which one is „Prva Strana Kosova“? The one we hear about every day in media outlets in Belgrade, and what the Kosovo Albanians and Kosovars in general are used to hear about?

Now I’ll answer the questions asked by your readers. Art has often preceded the overall developments, but also the alliances among societies, so I believe that if there is no political interference, even in the case between our two societies, art will precede the political processes. This happens in our daily lives, because we in the art scene of the Balkans have many things in common. As such, in international exhibitions abroad, artists from the Balkans are always together, so we are paving the way for overcoming prejudices and hatred between the Balkans societies, although it is almost impossible to do more when the will of the decision-makers is lacking.

How are the preparations for the Biennale in Venice going?

– Well, one can imagine the importance of being part of the Venice Biennale, but to represent your country means great responsibility besides the pleasure, because you don’t represent only yourself and your name but also the place where you come from and your nation. This was the main focus and presented the biggest task during the preparations.

It makes me very happy to have this opportunity but it has made me much more conscious during the preparation phase how important it is to share our experiences with the audience of the Venice Biennale, since we can be equal with other states (in terms of presentation) at least during the presentations in such an event. I have to say that we have a great team and we had full support by the Ministry of Culture, which was helpful, but as a project it is very challenging. Thanks to our team, Commissioner Arta Agani, Curators Vincet Honore and Anya Harrison, and many others who are working in the pavilion, I think we will make it and I hope we will have a dignified presentation.

What does it mean for you to be an artist in Kosovo today?

– Being an artist from Kosovo is challenging, just as it is in the entire Balkans, since art in society is often not seen as a priority because of the fundamental problems. It must be acknowledged that there is support for certain projects, but there is a lack of art markets, especially art collectors and commercial galleries that introduce and sell the works of artists. This phenomenon is not present only in Kosovo and in the Balkans, but also beyond. However, it is more evident in our region. What distinguishes us in the region are certainly the vast amount of original and interesting themes, we just have to find the ways to address them. The West has something, but we have something too.

- Questions asked by artist Vladimir Nikolic:

How much of your work has been done in Kosovo?

– In fact, most of my projects have been realized in Kosovo and with a team from Kosovo, apart from some specific projects and the ones I realized when I resided outside Kosovo. I believe that we as artists have to react to the place where we live, and I’m very focused on researching here. This research has often sent me out of Kosovo, but in most cases our artistic “actions” come from here.

Which ex-Yu artists do you have most contacts with?

– I have many contacts in all countries of the former Yugoslavia, especially with artists, curators and others who come from the fields of art. But it should be said that I got greater cooperation in Slovenia, specifically in Ljubljana, and also in Croatia. These were the first places in the region that opened their doors for my exhibitions and other presentations. I always mention that without the support from these two art scenes it would be all more difficult for me. However, I had some experience in other countries of the former Yugoslavia as well.

What is your main reason for staying in Pristina in spite of so many opportunities to move to some cozier part of the world?

– The work I do here makes me not think of leaving Pristina, because most of my projects are related to Kosovo. We can travel a lot but in the end, we have to come back and react here. This is more or less my slogan when I have discussions with younger artists or with my students.

I have thought of changing my environment for several times, especially when I was outside Kosovo in different residences for longer periods of time, because for quite some time I was half of the year in Kosovo, and half of the year outside it. This was very enjoyable and helped me with my work, since I was in Kosovo but I also had experiences and influences from abroad. I am not saying that I am going to stay in Kosovo forever, as it all depends on the work, but so far the realization of the projects has been much easier for me here. Although there are challenges for an artist who lives in a small place, I believe that for now I’m fine with living in Pristina and having frequent work trips.

Pratite nas na našoj Facebook i Instagram stranici, ali i na X nalogu. Pretplatite se na PDF izdanje lista Danas.